Portfolio

About

03/31/2020-Most of these samples are roughly 1-2 years old now. I’m not sure if I’ll update this soon or just focus on populating the projects section, but if interested I can provide more current samples of any of the following areas.

Below are code examples and a short excerpt about any difficulties faced in writing the code or design decisions made when designing the program. Some of the formatting is lost in the transition from Markdown to a Jekyll webpage. These excerpts are deliberately short and if longer samples are desired, please contact me. None of these code samples are perfect, and in some cases I have made significant improvements in my style and approach since writing them. I am always learning and improving, and in cases where the improvement is significant I point it out. This learning and improvement of the code I write is a constant process!

Documentation

Bash

#!/bin/bash

# SCRIPT

# Program 1: Matrix

# AUTHOR

# Adam Page

# DATE CREATED

# September 24, 2018

# DESCRIPTION

# This script performs basic file operations on tab

# and line separated numerical matrices. All output

# is sent to stdout. All error messages are sent to

# stderr and return appropriate exit codes.

# OPERATIONS

# (M = a matrix filename)

# dims M send the dimensions as "ROWS COLS"

# transpose M transposes a matrix (rows->columns)

# mean M gets the mean of each column

# add M M adds two similarly sized matrices

# multiply M M multiplies compatible matrices

# ERRORS

# 1 operation command not found

# 2 improper number of arguments

# 3 file does not exist

# 4 file not readable

# 5 matrix size mismatch for this operation

The important thing here is twofold: 1. the documentation of the header (and indeed the entire code) is organized, straightforward, and shows the user how to use this script and 2. as this is a script, the input and output of the script is explicitly stated. This is an interesting midpoint as it is a command line script, so most people using it will have at least basic scripting experience, but it also is an end user who will be using this script-thus it has elements of both an API and user documentation. I tend to favor API documentation that is clear to a programmer, and user documentation that is friendly to the user. What this means is API documentation includes things like high-level examples and (most importantly) accurate documentation of accessible function input/outputs. For user documentation I prefer descriptions, examples of use, and specifications that relate to using the software.

Scripting

Bash

# 5. Gives us a capability to read the memory.

echo "We will now read some memory from your process."

read -p "Enter a location to read: " LOC

read -p "Enter a number of bytes to read: " BYTES

gdb -q -p $PID --ex="x/${BYTES}ub 0x${LOC}" -batch | grep -e "^warning"

echo ""

This is part of an assignment written as a sort of proof of concept that memory outside of the specific process we’re in can be read, so long as the user has access to that process. This particular approach uses GDB, attaches it to the process in question, executes a command to get a certain number of bytes at a location, and filters out any warnings. This certainly isn’t the most technical example, but I actually struggled with this portion of this assignment until I found that GDB could actually read memory. I’d known about attaching GDB to a process before, but using it to read memory was new to me and it proved to be incredibly useful, making this portion of this assignment simple.

Basic Data Structures

C++

/**************************************************************************

* Method: remove(int)

* Description: Removes an element from the list at the specified index.

* exception: throws an InvalidElementException if index is out of bounds

**************************************************************************/

void remove(int);

// Removes an element from the list at the specified index.

void StringList::remove(int removeIndex)

{

// handle out of bounds index

if (removeIndex < 0 || removeIndex >= this->size())

throw InvalidElement(removeIndex);

if (removeIndex == 0) // handle removing index 0 (front) from the list

{

ListNode* temp = front;

front = front->next;

delete temp;

}

else

{

//find the node to be removed

int curIndex = 1;

ListNode* temp = front;

bool removed = false;

while (temp->next != nullptr && !removed)

{

// remove the node if its found

if (curIndex == removeIndex)

{

ListNode* deleteNode = temp->next;

temp->next = temp->next->next;

delete deleteNode;

removed = true;

}

// otherwise keep looking

temp = temp->next;

curIndex++;

}

}

}

This one’s pretty basic, but shows a basic data structure and a learning point for me. Its part of a linked list structure I wrote for strings. Obviously in C++ we would prefer a list that took any object type and the STL has plenty of structures that are more useful than this one, but the point here is that any programmer should be able to write a basic data structure, as well as modify them if needed. I think looking back at this code I wrote from almost a year ago, I’d say this code is over-commented. None of the comments really enhance the readability as they just restate what the code already says. I always strive to make code more readable, but comments should always be secondary to just writing code that is readable. If I do something that isn’t outwardly apparent, then I’ll comment it, but these days commenting every four lines is no longer something I find valuable.

System Programming (Linux)

C

/*

* runCommand

* Description: Takes a command and runs it in the

* foreground or background.

* param1: args - the command and arguments

* param2: arg_num - the number of arguments (including

* the command)

* return: the pid of the spawned process in the parent,

* nothing in main

* postcon: the command is executed in the child process

* or an error message is relayed

*/

pid_t runCommand(char **args, int arg_num, int background) {

// fork a new process - switch for parent/child

pid_t new_process = fork();

switch (new_process) {

case -1:

exit(1);

break;

case 0:

removeBackground(&args, &arg_num);

setupFileRedirection(&args, &arg_num, background);

if (background == 1) {

setupBackgroundSignals();

} else {

setupForegroundSignals();

}

execvp(args[0], args);

char *buff = malloc(sizeof(char) * 256);

strcpy(buff, args[0]);

strcat(buff, ": no such file or directory\n");

write(1, buff, strlen(buff));

fflush(stdout);

free(buff);

exit(1);

break;

default:

return new_process;

}

}

This is the command execution portion of a very limited shell I wrote. The full comment here is because this file has no header, as it is the main program. At a high level this is just basic use of the fork call in C, with proper handling for redirection and any options passed to the desired command. This program also included basic string parsing, basic signal handling, and reaping and reporting on child processes the shell created. Structurally I overdid this assignment a bit, and the code organization is such that there may be a bit more than is necessary for the assignment. I did this mostly because it makes the shell extensible; as the code is already organized should I choose to return to it and expand the functionality, I’m not stuck refactoring everything to allow for more files and code to be added without clutter. I almost always prefer this strategy, not only because file organization is just always important, but also because almost all programs written should be written in such a way that they can be extended or changed if that is needed or desired later. It makes the code more organized and it makes the future programmer (possibly myself) happier to upgrade or maintain the code.

Networking

C

/*

* clientGet

* Description: Sends the file requested to the client,

* or an error if the file isn't found.

* param1: datafd - the data socket file descriptor

* param2: client - the client to use

* param3: file - the filename requested

*/

void clientGet(int datafd, struct client_info *client, char *file,

char *client_name, uint16_t data_port) {

char *buffer = malloc(sizeof(char) * PACKET_SIZE + 1);

memset(buffer, '\0', PACKET_SIZE + 1);

char *control_msg = malloc(sizeof(char) * PACKET_SIZE);

memset(control_msg, '\0', PACKET_SIZE);

int filefd = open(file, O_RDONLY);

if (filefd == -1) {

printf("File not found. Sending error message to %s:%d\n",

client_name, data_port);

fflush(stdout);

sendError(FILE_NOT_FOUND_ERROR, client);

return;

}

printf("Sending %s to %s:%d\n", file, client_name, data_port);

int transfer_status = 0;

while ((read(filefd, buffer, PACKET_SIZE)) > 0 &&

transfer_status != -1) {

transfer_status = sendPacket(client, datafd, buffer);

free(buffer);

buffer = malloc(sizeof(char) * PACKET_SIZE + 1);

memset(buffer, '\0', PACKET_SIZE + 1);

}

close(filefd);

memset(control_msg, '\0', PACKET_SIZE);

sprintf(control_msg, "%d %d!", 0, 0);

write(client->socket_fd, control_msg, strlen(control_msg));

free(buffer);

free(control_msg);

shutdown(datafd, SHUT_RDWR);

}

Python

def get_control_msg(control_sock):

"""

Gets a single control message from the server

:param control_sock: the control socket to the server

:return: the string representing the server's control response

"""

response = control_sock.recv(10)

if chr(response[-1]) != '!': # check for ! end of control msg flag

response += control_sock.recv(10)

response = response.decode("ascii")

return response

These samples are part of a simple FTP server and client created to improve knowledge of sockets. I am by no means an expert network programmer, but I do understand the basics and can implement basic IPC. Improvements here could be better socket handling, and logging to a log file rather than to the command line from which the server was run. What I do like about this code is that it does one task (getting a file) in one method, by splitting some of the smaller tasks within the method into other methods. This kind of task decomposition is always important for readability as well as maintainability. Another nice thing is that the packet size is variable, although I’m sure there’s probably a better way than just setting it as a global which can be changed-it worked for this small-scale application, but I think when dealing with a larger network it would be much better to use a variable approach based on the network in question so all packets are handled appropriately.

Machine Learning

Python

def get_X(urldata):

"""

Get all of the X data we're using.

"""

mus = {}

sig_sqs = {}

host, mus['host'], sig_sqs['host'] = normalize(get_feat(urldata, 'host_len'))

url, mus['url'], sig_sqs['url'] = normalize(get_feat(urldata, 'url_len'))

dport = one_hot_port(get_feat(urldata, 'default_port'))

domain, mus['domain'], sig_sqs['domain'] = normalize(get_feat(urldata, 'domain_age_days'))

tokens, mus['tokens'], sig_sqs['tokens'] = normalize(get_feat(urldata, 'num_domain_tokens'))

ips, mus['ips'], sig_sqs['ips'] = normalize([len(ip) if ip is not None else 0 \

for ip in get_feat(urldata, 'ips')])

alexa, mus['alexa'], sig_sqs['alexa'] = normalize(get_feat(urldata, 'alexa_rank'))

scheme = one_hot_scheme(get_feat(urldata, 'scheme'))

path, mus['path'], sig_sqs['path'] = normalize(get_feat(urldata, 'path_len'))

port = one_hot_port(get_feat(urldata, 'port'))

mx, mus['mx'], sig_sqs['mx'] = normalize([len(mxhost) for mxhost in get_feat(urldata, 'mxhosts')])

ptokens, mus['ptokens'], sig_sqs['ptokens'] = normalize(get_feat(urldata, 'num_path_tokens'))

X = np.concatenate((host, url, dport, domain, tokens, ips, alexa, scheme, path, port, mx, ptokens), axis = 1)

return X, mus, sig_sqs

def f1_score(X, Y, Thetas):

AL, _ = forward_prop(X, Thetas)

Y_hat = np.round(AL)

true_pos = [1 if Y_hat.T[i] == 1 and Y.T[i] == 1 else 0 for i in range(len(Y_hat.T))]

true_pos = np.sum(true_pos)

pred_pos = np.sum(Y_hat)

precision = true_pos / pred_pos

false_neg = [1 if Y_hat.T[i] == 0 and Y.T[i] == 1 else 0 for i in range(len(Y_hat.T))]

false_neg = np.sum(false_neg)

recall = true_pos / (true_pos + false_neg)

false_ratio = false_neg / len(Y_hat.T)

f1 = 2 * ((precision * recall) / (precision + recall))

return f1, precision, recall, false_ratio

This is an example of getting features for a machine learning classifier for malicious URLs (based on features of the URL alone). The two included methods are the ‘X’ feature getter (or the training/validation/testing set, which are split up later) and the F1 score calculator. I chose the F1 score in this case as it is a good general metric. As mentioned in this writeup (about spam email, but the philosophy remains the same) I think that the user metric here depends on the user. For an experienced user, I would rather not filter out any valid URLs (increase precision, where false positives are very near 0), whereas for an inexperienced user I would prefer to filter out some potentially valid URLs if it also means filtering out nearly all malicious URLs (increase recall, where false negatives are very near 0).

Databases

SQL

-- team's worst enemy

SELECT wins.name, wins.total_wins, played.total_played,

wins.total_wins / played.total_played AS rate

FROM (SELECT w1.name AS name, SUM(w1.wins + w2.wins) AS total_wins

FROM (SELECT COUNT(g.match_id) AS wins, t.name AS name, t.id AS id

FROM game g

INNER JOIN team t ON g.dire_team = t.id

WHERE g.rad_team = 2163

AND winner = 1

GROUP BY g.dire_team) w1

INNER JOIN (SELECT COUNT(g.match_id)

AS wins, t.id AS id

FROM game g

INNER JOIN team t ON g.rad_team = t.id

WHERE g.dire_team = 2163

AND winner = 0

GROUP BY g.rad_team) w2 ON w1.id = w2.id

GROUP BY w1.id) wins

INNER JOIN (SELECT w1.name AS name,

SUM(w1.wins + w2.wins) AS total_played

FROM (SELECT COUNT(g.match_id) AS wins,

t.name AS name, t.id AS id

FROM game g

INNER JOIN team t ON g.dire_team = t.id

WHERE g.rad_team = 2163

GROUP BY g.dire_team) w1

INNER JOIN (SELECT COUNT(g.match_id) AS wins,

t.id AS id

FROM game g

INNER JOIN team t

ON g.rad_team = t.id

WHERE g.dire_team = 2163

GROUP BY g.rad_team) w2 ON w1.id = w2.id

GROUP BY w1.id) played ON wins.name = played.name

ORDER BY rate ASC

LIMIT 1;

This is what I would call a medium difficulty query that took a database of games played and produced the teams that a particular team is worst against. The hard coded team id 2163 was replaced in the application to make it more modular, but this query came from my pool of testing queries where I would run queries to build them and then test their validity. One of the nice things I’ve found about writing SQL is that in small and moderate size databases it is an iterative process by which I can get certain things, modify them, and finally arrive at what I want. I am generally a fan of this style of iterative development, and I favor agile methods and interactive languages (such as those with a REPL).

Problem Solving

Clojure

(defn check

"Checks a sudoku solution. If full-check? is true, does not allow for 0s

(which normally serve as unfilled spaces)."

[puzzle, full-check?]

(when (true? full-check?)

(if (contains? puzzle 0) false true))

(let [boxes {0 '(0 0), 1 '(0 3), 2 '(0 6), 3 '(3 0), 4 '(3 3)

5 '(3 6), 6 '(6 0), 7 '(6 3), 8 '(6 6)}]

(loop [i 0]

(if (<= i 8)

(if-not (and (check-line (m/get-row puzzle i))

(check-line (m/get-column puzzle i))

(check-line (apply concat

(m/matrix

(m/submatrix puzzle

(first (boxes i)) 3

(second (boxes i)) 3)))))

false

(recur (inc i)))

true))))

As the comment says, this pretty much just checks if a solution is true. I considered putting in the whole backtracker (very naive) solver that I implemented, but it is available on GitHub if you’re curious. Its not a particularly elegant solution to this problem, and I hope to improve it in the future. This particular method is just a means of checking to see that a puzzle has no errors, and in the case the full-check flag is true to check to make sure the puzzle is completely filled out by checking for the absence of the placeholder 0s.

Testing

Clojure

;;;; Sudoku Solver Tests

;;;; Author: Adam Page

;;;; Created: Dec 30, 2018

(ns sudoku.core-test

(:require [clojure.test :refer :all]

[sudoku.core :refer :all]))

;;; Environment and Variable Setup

(def prefixes

"Puzzle name prefixes."

["s01" "s02" "s03" "s04" "s05" "s06" "s07" "s08"

"s09" "s10" "s11" "s12" "s13" "s14" "s15"])

(defn add-sol-midfix

"Adds the _s to the prefix names which makes it a solution file."

[filenames]

(map #(str % "_s") filenames))

(defn end-filenames

"The adds all postfixes to the testing file names"

[prefixes]

(concat

(map #(str "sudokus/" % "a") prefixes)

(map #(str "sudokus/" % "b") prefixes)

(map #(str "sudokus/" % "c") prefixes)))

(defn add-extension

"Adds file extensions to the filenames for testing."

[filenames]

(map #(str % ".txt") filenames))

(def puzz-paths

"Puzzle pathnames."

(add-extension (end-filenames prefixes)))

(def sol-paths

"Solution pathnames."

(add-extension (add-sol-midfix (end-filenames prefixes))))

(def paths

"Puzzle and solution pathnames."

(map vector puzz-paths sol-paths))

;;; Tests

(deftest backtracker-tester

(testing "Testing the backtracker solver against all puzzles and solutions."

(is (every? #(= (get-puzzle (second %))

(backtracker (get-puzzle (first %)))) paths))))

This is a pretty basic test, but it just makes sure that the solution my sudoku solver matches the expected solution for previously solved puzzles. Clojure has a nice framework for testing, so much of this is just setup and running each test case. This is very simple unit testing based on known solutions. I have also written random tests on a unit-level scale. I am particularly interested in learning more about testing, as beyond unit testing I have less experience than I would like.

Design

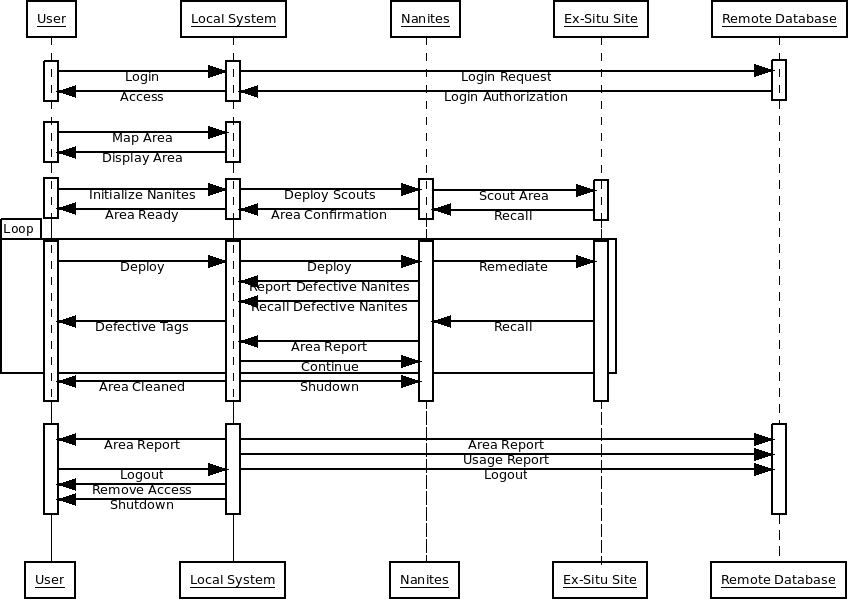

Message Sequence Diagram

This is a pretty simple message sequence diagram showing a user logging in and using a controller for nanite hardware. Much like the networking section I am not an expert at this type of design, but I do have the knowledge of basic diagrams and can read them to discern what a system needs. This case is particularly interesting as it involves a system with a local program, a remote database for authentication/updates, and an experimental piece of hardware the application is controlling.

Thank You!

Thank you for reviewing my portfolio! Please feel free to contact me through one of the means below:

Project maintained by adam-page Hosted on GitHub Pages — Theme modified from page-themes/midnight